The celebration of indigenous film at the 4th Native Spirit Festival

by Owen Van Spall

Fated to be overshadowed by the glamour of the overlapping London Film Festival, the 4th Native Spirit Festival, presented by Native Spirit Foundation, nevertheless offers a serious programme of films and cultural events exploring and celebrating the indigenous people of the world. Away from the BFI Southbank and the bustle of Leicester Square, the programme divides its time between the Amnesty International Human Rights Action Centre in Shoreditch, and the lecture theatres and screening rooms of SOAS and Birkbeck College.

The Native Spirit Festival is deigned as a counterweight to the distortion of the white man’s lens, featuring films not just about indigenous peoples, but by indigenous peoples. The backdrop to many of the films in the programme is the struggle to control the way indigenous people’s stories are told to the outside world, alongside the more tangible aims of economic development, education and compensation and preservation of a culture in the face of encroaching westernisation. These are not films with huge budgets, expensive CGI or any kind of major marketing campaign behind them. Many have a rough-and-ready, home-made feel (expect erratic subtitle tracks) and are often very subjective and personal rather than a BBC-type documentary.

The festival is part of the Native Spirit Foundation, established five years ago by Mapuche artist Freddy Trequil, a prominent member of the Mapuche community in Chile. The Native Spirit Foundation itself is a non-profit charity established and directed by indigenous peoples to support and promote their communities and educations. The Festival’s stated goals are to present “another outlook, another dimension”, to provide “a space of encounters for knowledge and wisdom as well as for the preservation of ancestral values… The festival will bring the strength of the elders, the joy of the children, and the poetics of their cultures. We as human beings are embodied in this earth and words with a heart resonate in us all”.

This year’s programme included such curiosities and highlights as Zapatista Autonomy: Another World is Possible takes viewers on a tour of the autonomous regions of the Zapatistas of Mexico, who are trying to separate themselves from their own government and form vibrant and surprisingly resourceful self-reliant communities after years of struggle and clashes with government security forces. Video Letters From Prison centres on one Lakota Indian family whose daughters being to record video letters for their imprisoned father who has been absent from their lives for over a decade, touching not just on universal and familiar daughter-father dynamics but exploring how the Lakota people reconcile dealing with family issues in their own traditional way but in a modern American setting.

Bran Nue Dae is an upbeat, frothy musical feature about an aboriginal boy who runs away from school and ends up on a surreal road-trip across Australia. Meanwhile, Year Zero takes viewers on a journey of a more unusual kind through the prophetic Mayan interpretation of the calendar, a very different way of looking at the cycles of the world. The viewer’s guide is Wandering Wolf, an elderly Mayan who now spends his time lecturing and touring globally, warning of the coming apocalyptic changes predicted to hit earth in 2012 – the fabled ‘year zero’ marking the end of the Maya calendar.

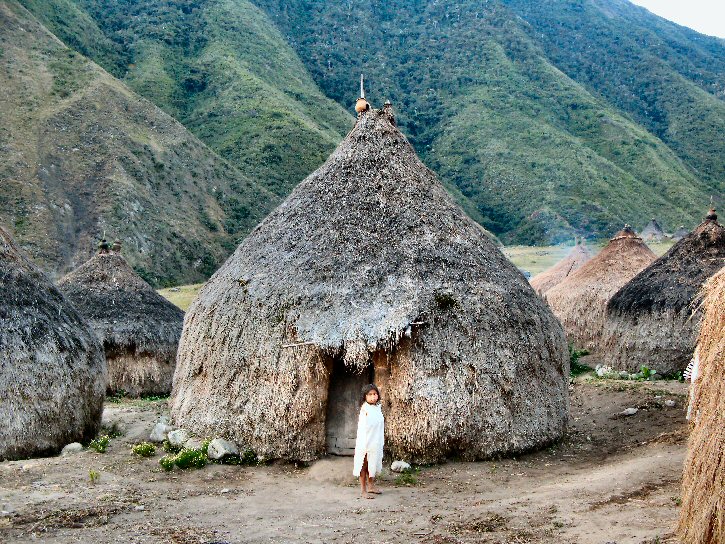

A late announcement at the close of the Festival was a special screening of the trailer for Aluna, presented by British director Alan Ereira. Ereira famously produced a BBC1 documentary on the Kogi people in 1990 and Aluna is a return to the subject matter, but this time it is produced by the Kogi people themselves. The Kogi are a lost civilization descended from the Inca and Aztecs and hidden on an isolated triangular pyramid mountain in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia, nearly five miles high on the Colombian-Caribbean coast. In 1990 they collaborated with Ereira to make the original 90-minute film about their tribe for BBC1, where they passed on their warning of humanity’s need to change course, to live in order to care for the world and keep its natural order functioning. Aluna is the Kogi’s attempt to say that “we did not actually listen to what they said. We are incapable of being changed by being spoken to. They now understand that we learn through our eyes, not our ears. In the face of the approaching apocalypse, they have asked Ereira to make a film with them which will take the audience on a perilous journey into the mysteries of their sacred places to change our understanding of reality.”

Cinema’s relationship with indigenous tribal peoples of Africa, the Americas and elsewhere has often meant the latter suffering either being patronised or portrayed as savages. Though these are undeniably more enlightened times, it is far too common even today to see tribal peoples on film and television presented as mere helpless victims of oppression waiting for salvation from kindly westerners. Native Spirit Festival’s mix of short films and lengthier documentaries continue to offer an illuminating and important alternative to the mainstream.

For more information about the festival and the foundation visit the official site.